Page Content

In 2013, the Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA) undertook a study of the working conditions of Alberta school leaders. Participating principals agreed to diarize their time for one week, 24/7. For a researcher, there is a hazard in asking busy people to document their time—namely, there is a good possibility that they will be too busy to describe why they are busy. Therefore, it was a real collective achievement to pull together 31 out of 50 invited participants. For at least one principal, study participation almost didn’t happen: “I attempted to do this survey twice before being able to complete it,” she said. “The weeks were too full of early morning meetings, full of late night school and system commitments. Combined with my regular workload there simply wasn’t time to collect and reflect on the data.”

In 2013, the Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA) undertook a study of the working conditions of Alberta school leaders. Participating principals agreed to diarize their time for one week, 24/7. For a researcher, there is a hazard in asking busy people to document their time—namely, there is a good possibility that they will be too busy to describe why they are busy. Therefore, it was a real collective achievement to pull together 31 out of 50 invited participants. For at least one principal, study participation almost didn’t happen: “I attempted to do this survey twice before being able to complete it,” she said. “The weeks were too full of early morning meetings, full of late night school and system commitments. Combined with my regular workload there simply wasn’t time to collect and reflect on the data.”

The task of diarizing how they spent their time for a whole week, in 15-minute increments, was likely just as challenging for the other 30 participating school leaders. The Pilot Administrators’ Time Diary Study was undertaken as a partnership between the ATA and its Calgary, Edmonton and Fort McMurray locals. The principals who participated represented a wide array of Alberta schools: elementary and secondary, urban and rural, privileged and struggling. Our findings showed, however, that principals shared the same frantic pace, making it difficult for them to stop, breathe and focus on the most meaningful and important aspects of their work.

Seven Dimensions of Leadership

Alberta Education’s (2009) Principal Quality Practice Guideline outlines the following seven dimensions of leadership:

- Fostering Effective Relationships

- Embodying Visionary Leadership

- Leading a Learning Community

- Providing Instructional Leadership

- Developing and Facilitating Leadership

- Managing School Operations and Resources

- Understanding and Responding to the Larger Societal Context

In practice, there are significant overlaps and affinities between these dimensions. However, each dimension is accompanied by descriptors, which may be used to develop measurable outcomes.

Evidence related to administrators’ work activities and workloads is timely. In fact, an impetus for this study was the pending implementation of some form of provincewide standards for school leaders. Alberta Education’s (2009) Principal Quality Practice Guideline articulates seven dimensions of school leadership. The document acknowledges the complexity of the administrator’s role and details the many competencies an administrator ideally brings to daily practice, as well as to long-term professional growth. But how does the reality stack up against the ideal? The time diary study was an initial effort to answer this question.

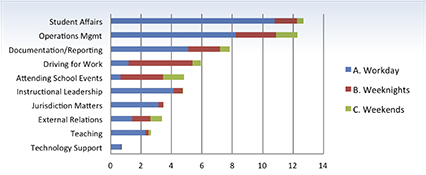

The principals who participated in this study worked an average of 58.5 hours per week (see Figure 1). It will surprise no school leader that study participants spent most of their time on issues related to student affairs (approximately 13 hours per week) and managing the school facility (12 hours per week). Notes in the time diaries suggest that many of these activities involved planned meetings and ad hoc interventions related to student special needs and student behavioural issues. Some time spent on student affairs was of a more positive nature: meeting with students about their programs of study, preparing for school events and celebrations, or driving students to extracurricular activities, for example.

The increased time required for documentation and reporting is commonly noted by experienced school leaders (Canadian Association of Principals, forthcoming; Cattonar et al 2007). Participants in this sample reported almost eight hours per week spent on this activity, with approximately three of those hours put in on evenings and weekends.

The three categories taking up the most of principals’ time (student affairs, facility management and reporting) made up almost 35 hours per week—the equivalent of five school days. Thus, these daily managerial tasks leave little time for the kind of leadership focus emphasized in The Principal Quality Practice Guideline (Alberta Education 2009). Managing school operations and resources is, after all, only one of the seven dimensions of leadership. The other six focus on leadership and learning—the priorities that school principals want to focus on but find consistently challenging (ATA 2009; Cattonar et al 2007; Tink 2004). This study, for example, found that an average of only about 4.5 hours per week was spent on instructional leadership.

The array of tasks diarized illustrates the complexity of the school principal’s role. The diaries were characterized by task-switching during day and evening hours approximately every two to four time blocks, or every 30 to 60 minutes. Longer periods of time with a single focus tended to occur only for structured activities (for example, jurisdictional meetings, staff meetings and school functions). There were few spaces of time in which principals were able to devote themselves to the leadership dimensions that would contribute in the long run to school improvement. Understanding and responding to larger societal contexts, and leading a learning community, for example, require time, thought and sustained attention. So, it is worth highlighting our participant’s comment that she was challenged to find the time not only to complete her time diary but also to reflect on its meaning. German sociologist Helga Nowotny (1994) describes how chronic “busy-ness” traps us in an “extended present”—spinning endlessly around the axis of now, at such a pace that we are unable to imagine or plan for the future. This seems an apt description of the life of the school principal, and it points to potentially large gaps between the ideal and the reality when it comes to leadership priorities.

The adoption of some form of leadership standards in Alberta is likely in the near future, but it is not at all clear how principals can develop the leadership savvy aspired to in The Principal Quality Practice Guideline (Alberta Education 2009), given their current working conditions. The findings from this pilot study suggest that, in its current form, the principal’s role is too time-consuming and too complex for all seven of the dimensions to be mastered by any one principal. The most heroic and dedicated might manage something like the 82 hours in a week worked by one of our study participants, but the literature on work–life balance and burnout suggests that such a pace is not sustainable (Duxbury and Higgins 2013).

The challenge of finding time to lead may become all the more pressing in the wake of Alberta Education’s (2014) release of the report of the Task Force for Teaching Excellence. Among the report’s recommendations are more professional development for principals and a stronger role for principals in evaluating teachers. Evidence from the time diary study, as well as other studies cited here, suggests that school leaders are already struggling to find time for the instructional leadership role. A forthcoming national study by the Canadian Association of Principals (CAP) includes many comments from principals that they find it difficult to spend time in teachers’ classrooms. In an ATA (2013) study, beginning teachers reported that they wanted more feedback on their practices than they were able to get. Teacher professional growth plans were valued for focusing professional development goals, but in many instances they were assessed in only a cursory way by school leadership. Classroom visits by administrators were less frequent than desired.

The Task Force for Teaching Excellence report calls for greater supervision responsibilities on the part of administrators, but it also recognizes that “more time and money must be found for the professional development of teachers and school leaders” (Alberta Education 2014, 40). Alberta Education might offer some funding for professional development, but it has historically been loath to implement sustainable, systemic reforms that would increase collaboration opportunities in schools—including opportunities for administrators to be the instructional leaders they want to be. The time diary study adds to research that consistently shows we are still a long way off from this ideal.

References

Alberta Education. 2009. The Principal Quality Practice Guideline: Promoting Successful School Leadership in Alberta. Edmonton, Alta.: Alberta Education. Also available at http://education.alberta.ca/media/949129/principal-quality-practice-guideline-english-12feb09.pdf (accessed May 20, 2014).

———. 2014. Task Force for Teaching Excellence: Part I: Report to the Minister of Education, Government of Alberta. Edmonton, Alta.: Alberta Education. Also available at https://inspiring.education.alberta.ca/wp-content/themes/inspiringeducation/_documents/GOAE_TaskForceforTeachingExcellence_WEB_updated.pdf (accessed May 20, 2014).

Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA). 2009. Leadership for Learning: The Experience of Administrators in Alberta Schools. ATA Research Update. Edmonton, Alta.: ATA. Also available at www.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/Publications/Research/PD-86-14%20Leadership%20for%20Learning.pdf (accessed May 20, 2014).

———. 2013. Teaching in the Early Years of Practice: A Five-Year Longitudinal Study. ATA Research Update. Edmonton, Alta.: ATA. Also available at www.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/Publications/Research/Teaching%20in%20the%20Early%20Years%20of%20Practice%20%28PD-86-19b%29.pdf (accessed May 20, 2014).

Canadian Association of Principals (CAP). Forthcoming.

Cattonar, B., C. Lessard, J.-G. Blais, F. Larose, M.-C. Riopel, M. Tardif, J. Bourque and A. Wright. 2007. School Principals in Canada: Context, Profile and Work: Pancanadian Surveys of Principals and Teachers in Elementary and Secondary Schools (2005–2006). Montreal: Chaire de recherche du Canada sur les métiers de l’éducation, Faculté des Sciences de l’éducation, Université de Montréal. Also available at https://depot.erudit.org/id/002032dd (accessed May 20, 2014).

Duxbury, L., and C. Higgins. 2013. The 2011/12 National Study on Balancing Work, Life and Caregiving in Canada: The Situation for Alberta Teachers. Edmonton, Alta.: Alberta Teachers’ Association. Also available at www.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/Publications/Research/COOR-94%20National%20Study%20on%20Balancing%20Work%20-Duxbury.pdf (accessed May 20, 2014).

Nowotny, H. 1994. Time: The Modern and Postmodern Experience. Trans. N. Plaice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Tink, G. 2004. “Administrators’ Workload and Worklife.” Master’s thesis, University of Lethbridge.

Laura Servage is a doctoral student in the Faculty of Education, University of Alberta.